- Home

- Nancy Isenberg

Fallen Founder Page 2

Fallen Founder Read online

Page 2

7. A Peep into the Antifederal Club (1793)

8. Newspaper announcement of Burr and Jefferson’s electoral tie

9. “Aaron Burr!” (1801)

10. Dueling Letter: Burr to Charles Biddle, 1804

11. Aaron Burr (1802), by John Vanderlyn; James Wilkinson (1796), by Charles Willson Peale

12. Aaron Burr’s travels in the West, 1805–1806

13. The capture of Aaron Burr

14. Aaron Burr (1826), by Henry Inman

The College of New Jersey in 1776

Chapter One

A MAN OF PROMISING PARTS

People are always looking for the man in the child without considering what he is before he becomes a man.

—Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile, or On Education (1762)

In 1793–94, Gilbert Stuart, best known today for his unfinished likeness of George Washington, painted a portrait of a promising politician. There is something unconventional about this particular canvas: age and authority do not quite coincide. The perfectly proportioned face, its flawless skin rose-tinted and glowing, suggests a man in his early twenties. Only the receding hairline hints that he might be older. One other pronounced feature stands out: the large hazel eyes, with coal black pupils, that gaze intently from the canvas. (See the book’s jacket for portrait.)

The man in the portrait is thirty-seven-year-old Senator Aaron Burr of New York. Two years earlier, he had come into office by defeating Philip Schuyler, a powerful, wealthy landholder twenty-three years his senior. Schuyler was deeply resentful about the unexpected turn of events. These two men could not have been more unalike: the elder was hulking and unapproachable, his victorious opponent not just younger but elegant and engaging.1

Appearances mattered in the politically tumultuous 1790s, and Burr’s decision to commission the portrait marked more than the entry of a newcomer into the republican ruling class. Stuart’s carefully composed image of Burr announced a new democratic ethos: none of the outward emblems of social status appears in the portrait. The youthful Burr is without a wig. His dress is remarkably plain: no lacy frills, no gold buttons, no richly dyed satin cloth. Stuart tellingly observed that his American clients demanded accurate and realistic representations of themselves—none of the costumes, insignia of office, and “Grand Manner” setting associated with British portraiture.2

Burr represented a new era. So-called “natural aristocrats” had stepped in, where before the Revolution only the traditional landed elite had stood. The new leadership core was composed of enlightened readers, disciples of an American nationalism, whose rise coincided with the adoption of the federal Constitution. Aaron Burr projected the image of a man of possibilities, a mirror of the energetic young nation that he represented in the Senate. At the same time, the political world that Burr entered was fiercely competitive, as a new partisan climate emerged that relied on nasty public attacks, the circulation of vicious rumors, and occasionally led to duels. A young man of promise could just as easily provoke envy and anger, if he became too prominent, or was perceived as threatening other politicians, especially those who already were in power.

The new ruling elite consciously fashioned themselves as suitable leaders. Though the image of defiant children rebelling against the “mother country” had been a seductive metaphor during the long war for American independence, celebrating youthful rebellion was a less compelling refrain once the new United States government tried to shore up its symbols of national authority. Indeed, though the Revolution had been waged by young men, the act of nation building became enshrined as the province of fathers. As George Washington assumed the presidency in 1789, he was styled the “friend and father” of his country. Today we still idolize the founders as austere and wise, and long past their days of youthful excess and indulgence. Burr, in contrast, is almost always portrayed as a man who still exudes a romantic vitality.3

Stuart was not alone in fashioning an image of Burr that emphasized his youth. As he grew older, Burr was pleased to recall several childish escapades from which later biographers took their cue. Thus, he was often described as defiant and mischievous. A favorite story he told concerned the time he tried at the age of ten to run off to sea. He had outmaneuvered his uncle and guardian, who then climbed aboard ship to fetch his errant ward. Hoisting himself to the top of the ship’s mast, the lithe young boy skillfully negotiated a truce on his terms: His uncle agreed to let him return home without a beating. Here was a childhood memory to preview his future as a courtroom attorney—that is, as a master of rhetorical persuasion, active and tireless, who was prepared to go to great lengths (or heights) in order to gain the upper hand.4

Burr’s unusual relationship with his older wife Theodosia Prevost (she was ten years his senior) further reinforced the notion of his perpetual youthfulness. By marrying a mature woman, he appeared to have skipped over the “normal” stages of development. The contrast between them must have made him appear even younger. Burr was considered for the vice presidency as early as 1792, to contest the incumbent vice president, John Adams, nearly a quarter century his elder; but his name was ultimately dropped because of his relative youth. As his political career went forward, Burr surrounded himself with a corps of energetic younger men. They, too, celebrated his youthful exploits, still praising him in 1804 for having joined the army as a mere “boy,” and standing in the forefront of those who “drew their swords at the opening of the revolution.” The “boy” was a man of forty-eight when his “little band” issued this reminder of his adolescent feats.5

Youth, age, and appearance had political significance, conditioning how public and private character was judged and measured. Burr’s youthfulness was relevant, as personality itself became a more crucial quality in shaping electoral politics in the nascent American democracy. Burr became known as a man who achieved a lot early in life; his precocity set him apart. In that sense, his childhood had lasting consequences.

“A LITTLE DIRTY NOISY BOY”

Aaron Burr was born in Newark, New Jersey, on February 6, 1756, in the middle of winter. His mother, Esther Burr, recorded in her journal that he arrived “unexpectedly.” Presumably, she had wanted her husband to be present for the birth, but it had “pleased God” that her son should make his entrance when his father was away from home. She found this birth a “gloomy” event, enduring labor “destitute of Earthly friends—no Mother—no Husband.”6

Burr’s family was a rather unusual, and extremely tight-knit, family. His father, Aaron Burr, Sr., had been educated at Yale. A Presbyterian minister since 1736, he was now president of the College of New Jersey (today’s Princeton University). On assuming his duties in 1748, only three other men in the American colonies were serving as presidents of colleges. Despite his small stature, the senior Burr was known for preaching in a “powerful manner” to the large flock that gathered at his meetinghouse. His wife described her husband’s performance this way: “nature seems to bubble up and overflow into expression.”7

Burr’s mother was a remarkable woman. She was the daughter of the Reverend Jonathan Edwards, the most influential theologian in America, and herself an independent spirit. One contemporary said she possessed an “unaffected, natural freedom,” and that “her genius was more than common.” She had “a lively, sprightly imagination, a quick and penetrating discernment,” the same observer added. “She knew how to be facetious and sportive, without trespassing on the bounds of decorum.” The Burrs did not fit the typical profile of a dour Calvinist family. Esther Burr displayed a passion for life. She was not shy about expressing her opinions, nor could she be categorized as a retiring matron. She was deeply religious, without being stuffy, a clever conversationalist with a mind of her own.8

Esther’s detailed journal, almost 300 pages long, was filled with witty comments on religion, literature, and politics. In these pages, she defended her sex, in one case opposing a tutor at the college for

making disparaging comments about women. She found it appalling that the man had insisted that women were incapable of understanding “anything so cool and rational as friendship.” She would hear none of it, noting that she had “retorted several severe things upon him,” which made him flustered and caused him to go off in a huff. Her confidence was unusual, but not out of character. She came from a proud family, and her father had closely supervised the education of every one of his children. She could be quick to act—it took her only five days to accept her future husband’s proposal of marriage. She was twenty, he was thirty-six, but she willingly left Massachusetts for a new life in New Jersey.9

The Burrs were living in Newark at the time Esther gave birth to her son. Aaron had a sister, Sally, who was two years older. By the end of his first year, when the college building was nearing completion, the family moved to Princeton. Esther Burr wrote with a rare candor in her journal, saying that “Aaron is a little dirty noisy boy” and “very different from Sally in almost everything. He has more sprightliness than Sally & most say he is handsomer, but not so good tempered.” Her childrearing methods were rigid and unyielding; her “mischievous” little son was “very resolute and requires a good governor to bring him to terms.” Physical punishment was readily applied to both children.10

At the same time, Burr’s mother looked at her son as special—a survivor. At eight months, he had become gravely ill. She had little hope, but somehow he recovered. She wrote powerful lines in her journal: “I look on the Child as one given to me from the dead. What obligations are we laid under to bring up this Child in a peculiar manner for God?” Before he was old enough to talk, he was thought to be a fortunate soul.11

The Burr household would not continue to be so blessed. On September 4, 1757, Aaron Burr, Sr., rode to Elizabethtown, New Jersey, to preach the governor’s funeral sermon. When he returned the following day, he became seriously ill, and never summoned enough energy to leave his bed. He died on September 23. A few weeks later, Esther recorded that “my little son has been sick . . . and has been brought to the brink of the grave.” But little Aaron survived once more. After her husband’s death, Esther’s own father, the Reverend Jonathan Edwards, moved to Princeton to replace him as president of the college; yet he was next, struck down by smallpox in March 1758. Though Esther Burr and her children had all been inoculated, she barely outlasted her father, dying on April 7. If that was not enough tragedy for one family, Sarah Edwards, Esther’s mother, came to Princeton to collect the family’s belongings and to take charge of her grandchildren, when she, too, became ill with dysentery, and died on October 2. In little over a year, Burr had lost his parents and his grandparents. Aaron and his sister Sally were now orphans.12

“AND LEARNS BRAVELY”

Burr left few memories about his childhood, and he wrote nothing about his parents. Precocity and perseverance—achieving well beyond one’s age or assumed capacity—nevertheless marked his youth. In everything he later wrote to his own daughter, he voiced an urgency, intensity, and insistence on her “determination and perseverance in every laudable undertaking.” His sense of personal calling and inner resolve give us some clue about his early education. Time or talents could not be wasted. Nothing could be left to chance. Burr’s urgency, a desire to excel at an early age, reveals something essential about his childhood.13

A family friend, Dr. William Shippen of Philadelphia, temporarily cared for the two orphans. In 1760, two years after the death of his parents, Aaron and his sister were placed under the guardianship of their uncle, Timothy Edwards, Esther’s younger brother. The two children suddenly found themselves in a large alternative family. In addition to Aaron and Sally, Timothy and his new wife Rhoda Ogden gained custody of all of Timothy’s surviving siblings. As it turned out, death had dissolved two families—Burr’s immediate family, and that of his grandparents. In the reconstituted Edwards household, presided over by Timothy, Burr was the youngest, surrounded by five aunts and uncles, who ranged in age from twenty to ten years old. Almost immediately, Timothy Edwards’s brood increased again. He took in two additional charges, his wife’s younger brothers, Matthias and Aaron Ogden.14

Death is a potent reminder that life is short and the future is unpredictable. Burr learned this lesson early. Competing for recognition in a crowded household, he grew in determination. When Burr was seven, his uncle Pierpont Edwards described him as an avid scholar, writing that he was “hearty, goes to school, and learns bravely.” Burr’s most vivid childhood memories curiously focused on episodes in which he ran away from home. The young Burr was always eager to prove himself to his family.15

Burr’s family background reinforced his commitment to education. The exacting theologian Jonathan Edwards had professed a personally demanding religious faith to those around him. The grandfather’s “awakened” gospel commanded a full knowledge of salvation at an early age. The theologian had been openly criticized in 1740 for “frightening poor innocent children, with talk of hell fire, and damnation.” But he withstood this criticism: to hold onto naive views, Edwards believed, only left children vulnerable to suffering an eternity in hell. Children were not simply sinners in God’s eyes; they were intelligent beings capable of persuasion and reflection. Jonathan Edwards treated his own children—including Esther and Timothy—as pupils, instructing them according to their “age and capacity,” training their agile minds as quickly as possible. With death looming large, there was a real urgency to save children before it was too late. It seems likely, then, that Timothy Edwards shared the same urgency about education as his father and instructed Aaron and his sister accordingly.16

Burr’s childhood was unusual in another sense. Though they died when he was little more than an infant, he could read testimonials to his parents’ uncommon virtues. In death, his father was eulogized for his “industry, integrity, strict honesty, and pure undissembled piety.” He was a Christian man of action—scrupulously honest and endowed with an unblemished moral character. Such glowing memorials offer a startling contrast to his son’s eventual reputation, for the promising Aaron Burr would be tarred and feathered in historic memory as a ruthlessly ambitious, dishonest, dissembling public official, and a hedonist in his private life.17

Timothy Edwards raised Burr to follow in his father’s footsteps. There was little social mobility in the eighteenth century, and few young men imagined selecting a career that was different from their fathers. The rather remarkable achievements of Benjamin Franklin, moving in leaps and bounds from his father’s status of tradesman to that of international celebrity and one of the wealthiest men in America, were rare indeed.18

Aaron Senior and Junior both grew up as orphans of means. Aaron’s father had been the youngest of the thirteen children of Daniel Burr, a wealthy and respected landowner in Fairfield, Connecticut. His father died when he was six, and his father’s patrimony allowed him to attend Yale College. Burr Senior left his namesake an inheritance of £3,679, which was used to support his son’s education. Neither Aaron truly knew his father, though each knew of his father’s reputation as a gentleman. They understood, as young men, that they were expected to become “men of letters.” One chose the church, the other the bar, but both honed their manners and skills of persuasion so as to maintain their standing among the elite of society.19

KITH AND KIN

Burr spent his first two years under Timothy Edwards’s roof in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and the remainder of his early years in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. Edwards appears to have been a devoted guardian. In 1762, upon returning to New Jersey, he took up the practice of law. He was clearly prosperous enough to support his growing family, as he and his wife would eventually have fifteen children. His uncle nevertheless made sure that young Aaron gained a solid education. He took the unusual step of hiring a Princeton graduate, Tapping Reeve, to supervise the instruction of both Aaron and Sally. Reeve was appointed master at the local Presbyterian academy, Edward

s served on the board of visitors, and Aaron enrolled at the age of seven.20

Situated along the river of the same name, Elizabethtown was a fairly prosperous colonial town. It was later the home of William Livingston, longtime governor of New Jersey, who served from 1776 until his death in 1790. He had been a close friend of Aaron’s father, giving the eulogy at his funeral. A native New Yorker, Livingston was a member of the one of the largest landholding “manor” families in the Empire State. Livingston was an avid supporter of the College of New Jersey (Princeton), and the first classes of the institution were held in Elizabethtown. Not unlike many of the other elite members of the community, he sided with the “New Light” Presbyterians, or “Dissenters,” as the branch that followed Jonathan Edwards were called. The Elizabethtown Presbyterian Church became a symbol of the town’s Revolutionary as well as dissenting religious heritage.21

Presbyterianism, the college, and a conservative political ruling class represented the three pillars of the social order in Elizabethtown before and after the Revolutionary War. Burr’s stepmother was Rhoda Ogden Edwards. Her father, Robert Ogden, was a leading member of the political and religious elite in Elizabethtown. His sons, Robert, Matthias, and Aaron, all attended Princeton, fought for the patriots’ cause, and went on to practice law—taking the same professional path as their cousin Aaron Burr.22

In this small but influential Revolutionary community, Burr made lasting connections with the sons of the town fathers. Matthias and Aaron Ogden, who were close to him in age, grew up in the same household. They were more like brothers than cousins. Another boyhood friend from Elizabethtown was Jonathan Dayton (Dayton shared Burr’s youthful ambition, and would later be the youngest delegate sent to the Constitutional Convention in 1787). The bond of friendship among Burr, Dayton, and the Ogden boys was sealed when Matthias married Hannah Dayton, Jonathan’s sister. As two of the most prosperous families in town, the Daytons and Ogdens occupied the best pews in the Presbyterian Church. Dayton attended Princeton, which completed the inner ring of Burr’s boyhood band.23

White Trash

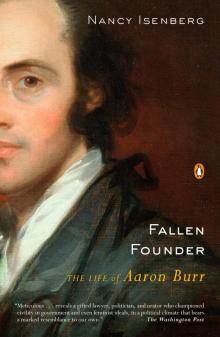

White Trash Fallen Founder

Fallen Founder